Faster, Sooner. Climate Change Shrinking Himalayan & Andean Glaciers, Rivers

New research by The Ohio State University in the US has sounded a warning for the residents in the Himalayan and Andes regions which are the world’s highest and the longest mountain ranges.

They have found that the glaciers of Andes mountains and the Tibetan plateau are melting more rapidly than any point in the last 10,000 years-which means water supply in the parts of Peru, Pakistan, China, India and Nepal will decline and soon.

“Supply is down. But demand is up because of growing populations,” said Lonnie Thompson, a climate scientist at Ohio State’s Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center. “By 2100, the best case scenario is that half of the ice will disappear. Worst-case scenario: two-thirds of it will. And you’ve got all those people depending on the glacier for water.”

The research head Thompson who calls the Tibetan plateau as the ‘third pole’ is worried about the findings.

There have been times throughout history when the glacial ice cores showed temperatures increased—during an El Nino, for example. But within the last century, the cores from both the Andes and the Himalayas show widespread and consistent warming.

“This current warming is not typical,” Thompson said. “It is happening faster, it is more persistent and it is affecting glaciers in both Peru and India. And that is a problem because a lot of people rely on those glaciers for their water.”

Melting glaciers can trigger such hazards as avalanches and floods. And they also can have long-lasting effects on a region’s water supply in parts of Afghanistan, Bhutan, China, India, Nepal, Pakistan and Tajikistan.

“There are 202 million people in Pakistan who rely on water from the Indus River—and that river is fed by the glacier.

The effects in Peru, too, could be far-reaching, particularly on Peruvian agriculture and on the water supply in Lima, the Peruvian capital.

Thompson and his team are hoping that by studying the glaciers in both areas, they will find answers to slow glacial retreat—or to provide new water sources to at-risk areas. They are hopeful that they can find solutions to help both places.

Climate Vulnerability Assessment for the Indian Himalayan Region By the GOI

Another research by the Indian government, done by the Department of Science and Technology (DST) in their vulnerability assessment pinpoints that the Himalayan state of Assam is most vulnerable to Climate change. The study was part of the Swiss-funded Indian Himalayas Climate Adaptation Programme (IHCAP).

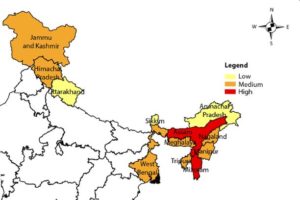

As per the assessment, the “vulnerability index is found to be the highest for Assam and Mizoram, followed by Jammu and Kashmir, Manipur, Meghalaya and West Bengal, Nagaland, Himachal Pradesh and Tripura, Arunachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand”. “Sikkim is the least vulnerable state,” the assessment found.

The Himalayan mountain range is the tallest in the world. It covers an area of about 4.3 million square kilometers and nearly 1.5 billion people depend on it.

The study highlighted that the Himalayan ecosystem is vital to the ecological security of the Indian landmass. Himalayas support about 20 percent of the world’s population and is a storehouse of the third highest amount of frozen water on earth. The tall mountains play a crucial role in providing forest cover, feeding perennial rivers that are the source of drinking water, irrigation, and hydropower, conserving biodiversity, providing a rich base for high-value agriculture and spectacular landscapes for sustainable tourism.

But, as per the study, mountainous regions are one of the most fragile environments across the world and other preliminary studies reveal that the IHR will experience higher levels of climate change and its associated impacts.

The study adds to the almost unendingly pessimistic prognosis for water in the Indian subcontinent where groundwater depletion has also been flagged as a serious crisis building up by as early as 2020. With monsoons becoming more erratic on top of everything else, its clear that water management is a hot button topic no one can run away from anymore.