Problems for River Ganga Persist Despite ODF Status

According to Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) assessment, domestic sewage from towns and villages along the Ganga is the main source of pollution (over 70%) in the river rest comes from Industrial Effluents. But recently all 4,480 villages on the banks of River Ganga have been declared open defecation free (ODF) under ‘Namami Gange’ initiative. Making villages and towns along the Ganga river ODF was a critical part of the Swachh Bharat Mission (SBM). Officials had banked that the ODF can bring down a load of fecal matter entering the streams.

As the major electoral promise’s deadline approaches, Ganga has again come into the limelight of our country’s polity as a major success.

Experts, on the other, say the battle is half won. “Making toilets is the first step. But the challenge is to contain pollution from fecal waste. This would only be possible if we treat and reuse our waste safely, and avoid dumping in the river in any form,” says Suresh Rohilla, a senior director with Delhi-based non-profit Centre for Science and Environment.

Currently, most of these villages and towns don’t have sewage systems. Untreated fecal waste is just dumped around, once taken out of tanks. It then continues to flow into the river defeating the very mission of making the river basin ODF.

The urgency of addressing this issue can be gàuged from the fact that towns and villages close to the river generate 180 million litres of fecal sludge every day. The river can’t be rid of pollution unless cities and villages along the river fix the glitches in fecal sludge management.

Sunita Narain, director general of CSE, said: “A country like India cannot allow a single drop of its precious and limited water to be degraded. But that is exactly what is happening – our rivers and lakes, and our groundwater are getting increasingly polluted. She further added, “Our challenge of having a ‘Clean India’ will not be met just by building toilets, but by building entire sanitation systems that are sustainable and affordable for all. Only then will we be able to protect our water.”

In Uttar Pradesh, a major focus state for cleaning Ganga, 80% of the septic tanks are connected to open drains, which ultimately open into rivers. The UP Action Plan for 2017-2020 says that the state’s cities have 80% toilet coverage. But most of them don’t have a sewage system, including many towns and cities along Ganga.

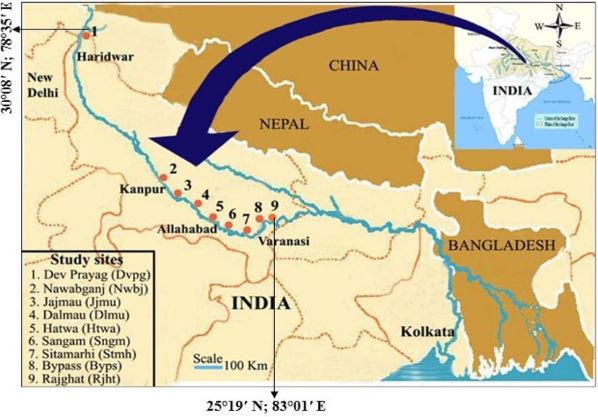

The thinktank estimates that in cities like Allahabad, Varanasi and Kanpur, hardly 25% of fecal sludge generated is collected for safe disposal. For example, in Varanasi, 246 kilolitres of fecal sludge is generated every day, but only 30 kilolitres is collected for safe disposal.

Along the main stem of Ganga river there are 30 million toilets with tanks. This doesn’t necessarily mean that all of them are under safe fecal sludge disposal and management. “It is a reality that most are dependent on on-site containment of our fecal sludge. The need is to make this reality safe by ensuring proper sewage management,” says Rohilla.

Way Forward

Indian govt in 2017 declared a national policy on fecal sludge and septage management(FSSM); where every state is supposed to adopt an FSSM action plan. D.S. Mishra, secretary, Union ministry of housing and urban affairs, pointed out that the government has managed to build 95% of the stipulated number of toilets – but that is not an end in itself. “Much more needs to be done, including bringing in systems to ensure the waste from these toilets does not end up polluting our land and water resources. That is where FSSM – fecal sludge and septage management systems – come in. They are the only cost-effective way of taking care of this waste.”

In this backdrop, FSSM plan in Odisha outshines other states. This pilot programme was implemented with support from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF), Arghyam, Centre for Policy Research and Practical Action. Since 2016, the initiative has been scaled up to nine other towns under the Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation (AMRUT).

Six septage treatment plants (SeTPs) were commissioned on October 26, 2018, and six others are in progress, which together will cater to 60% of the Odisha’s urban population. All these SeTPs are based on low energy-consuming technologies to ensure minimal operation and maintenance cost. Recently, Odisha decided that all Urban Local Bodies(ULBS) will adopt the FSSM approach and will set up septage treatment facilities.

Under the FSSM Framework, capacity-building interventions have been rolled out. Like strengthening of various grassroots-level institutions such as the Slum Sanitation Committee, Ward Sanitation Committee and City Sanitation Task Force (CSTF) to ensure community ownership in sanitation service and people-centric sanitation service delivery systems in the ULBs. ULB officials, Community Based Organisations (CBOs) and community leaders have also come together to create community engagement models in urban sanitation.

We do agree that much more now needs to be done to ensure quick grounding of such initiatives to achieve universal coverage of safe human waste disposal in all urban areas. The sanitation challenge in India is complex and large in scope and scale. However, if we can encourage the involvement of govt, Local bodies, ULBs, global organizations and most importantly, local communities, who have taken it upon themselves to collaborate and “own” these initiatives, the country may solve its Sanitation challenge and save precious Rivers and water in the process.