More with less. Growing CO2 could reduce nutrition levels of crops

Losing the goodness?

Losing the goodness?

According to a new study led by the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, rising levels of carbon dioxide (CO2) from human activity are making staple crops such as rice and wheat less nutritious and could result in 175 million people becoming zinc deficient and 122 million people becoming protein deficient by 2050.

The study also found that more than 1 billion women and children could lose a large amount of their dietary iron intake, putting them at increased risk of anemia and other diseases.

By 2050, India is expected to be the world’s most populous country, will also bear the greatest burden. “India alone is the largest contributor to all 3 nutritional vulnerabilities: 50 million additional people to the newly zinc-deficient population, 38 million newly protein deficient, and 502 million women of childbearing age and children under 5 who are vulnerable to disease resulting from increasing iron deficiency,” the research, published on 27 August in the peer-reviewed scientific journal Nature Climate Change, said.

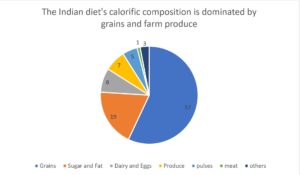

The Indian diet predominantly comprises wheat, the lesser-nutritious polished white rice, pulses and vegetables. Besides, India has the world’s second lowest meat consumption, a key provider of proteins and iron. The following pie chart shows that the Indian diet’s calorific composition is dominated by grains and farm produce.

So this finding is alarming for a country already struggling with a high mortality rate among new borns and malnutrition among females and children. In a Unicef report India stands at rank 12 with 25.4 deaths per 1,000 births.

Presently, more than 2 billion people worldwide are estimated to be deficient in one or more nutrients. The researchers also emphasized that people currently living with nutritional deficiencies would likely see their conditions worsen as a result of less nutritious crops.

Climate change is already known to threaten food security as extreme weather events can cause crop failures. This research brings to light how it can further add to the problem worsening malnutrition.

“One thing this research illustrates is a core principle of the emerging field of planetary health,” said Myers, who directs the Planetary Health Alliance, co-housed at Harvard Chan School and Harvard University Center for the Environment. “We cannot disrupt most of the biophysical conditions to which we have adapted over millions of years without unanticipated impacts on our own health and well being.”

To this end, the recent unlocking of the wheat genome, and previous work on other staples becomes even more vital, as scientists can now try and compensate for the drops by tinkering with the crop genome to make it more nutritious and effective.