Global Study Shows World’s Shrinking Wilderness

Want it ? Pay a Toll, says Brazil

Want it ? Pay a Toll, says Brazil

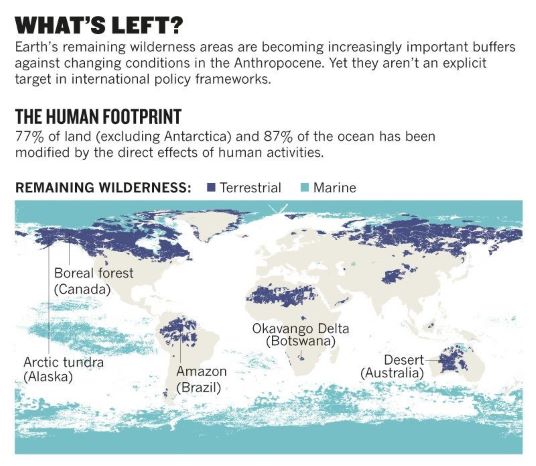

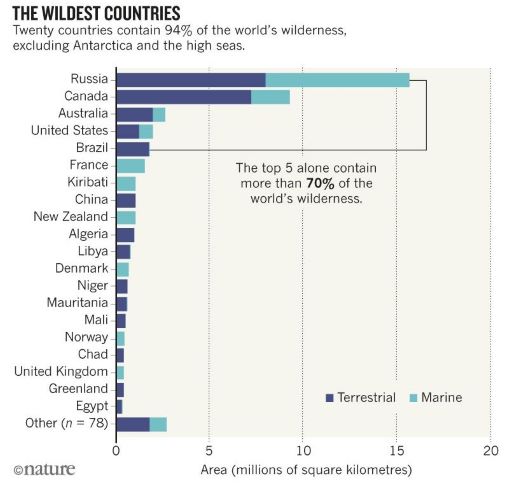

With man’s insatiable need for food, land, and other resources there is less than a quarter of land and even less oceans that are left untouched by humanity. Research by US and Australian scientists have highlighted that just 23% of the planet’s land surface (excluding Antarctica) and 13% of the ocean can now be classified as wilderness, representing nearly a 10% decline over the last 20 years. And more than 70% of what wilderness remains is contained within just five countries.

A century ago, only 15% of Earth’s surface was used to grow crops and raise livestock. Today, more than 77% of land (excluding Antarctica) and 87% of the ocean has been modified by the direct effects of human activities.

An area of terrestrial wilderness larger than India — a staggering 3.3 million square kilometers — was lost to human settlement, farming, mining and other pressures. In the ocean, areas that are free of industrial fishing, pollution and shipping are almost completely confined to the polar regions.

Numerous studies are revealing that Earth’s remaining wilderness areas are increasingly important buffers against the effects of climate change and other human impacts. But, so far, the contribution of intact ecosystems has not been an explicit target in any international policy framework.

Wilderness areas are now the only places that contain mixes of species at near-natural levels of abundance. They are also the only areas supporting the ecological processes that sustain biodiversity over evolutionary timescales. As such, they are important reservoirs of genetic information, and act as reference areas for efforts to re-wild degraded land and seascapes.

Safeguarding intact ecosystems is also key to mitigating the effects of climate change. Many wilderness areas are critical sinks for atmospheric carbon dioxide. For example, the boreal forest is the most intact ecosystem on the planet and holds one-third of the world’s terrestrial carbon. And intact forested ecosystems are able to store and sequester much more carbon than are degraded ones. In the tropics, logging and burning now account for up to 40% of total above-ground carbon emissions. In the ocean, seagrass meadows that are degraded (such as by sediment pollution) switch from being carbon sinks to major carbon sources.

This must change if we are to prevent Earth’s intact ecosystems from disappearing completely. So while global maps are useful for drawing attention to the attrition of wilderness areas, only the greater detail of national and local maps can really help us understand and respond to the threats that face our remaining wild areas. Local level policy interventions, Mechanisms that enable the private sector to protect, rather than harm wilderness areas, or establishing protected areas in ways that would slow the impacts of the industrial activity on the larger landscape or seascape are some of the ways the research has suggested to help secure the wilderness before it disappears forever.