EU Proposes Ban On Over 90% of Microplastics Pollutants

A wide-ranging ban on microplastics covering about 90% of pollutants has been proposed by the EU in an attempt to cut 400,000 tonnes of plastic pollution in 20 years. The proposed law would restrict the use of intentionally added microplastics under the European regulatory system, REACH, which sets out the chemicals authorised for use in Europe and in what concentrations they are permitted.

The European Chemicals Agency (ECHA), which has tabled the new law, is claiming that if adopted, it would prevent an estimated 400,000 tonnes of microplastics from entering the environment over the next 20 years.

According to ECHA, 10,000 to 60,000 tonnes of primary microplastics enter the environment every year in Europe – that’s microplastics that were intentionally added to products, as opposed to the ‘secondary’ microplastics that come from the degradation of larger plastic debris.

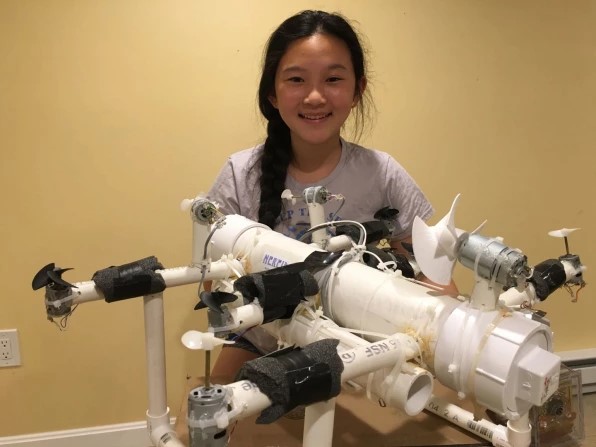

Microplastics are tiny pieces of plastic less than five millimeters in diameter, often found in cosmetics and personal care products. They can also be used in paints, detergents, medical products and elsewhere, meaning the minuscule plastic pieces find their way into the environment from a vast array of everyday sources – often without consumers being fully aware of the impact of their products.

Globally, according to a 2016 study by Eunomia Research and Consulting, primary microplastics make up almost 13 percent of the 12.2 million tonnes of plastic ending up in the marine environment every year.

Research has shown that microplastics are now present all across the food chain. Less discussed but more common, primary microplastics also concentrate in terrestrial environments, accumulating in sewage sludge that ends up being used as fertilizer. Once in the environment, they are next to impossible to remove.

Several EU member states have already introduced their own restrictions on microplastics. In the UK, a ban was introduced in January 2018, which the government described as ‘one of the world’s toughest’. Like many microplastics laws, the UK ban focuses on the microbeads in rinse-off cosmetics like face wash and shower gel – the proposed EU law appears to be much more comprehensive, looking at a wider range of products and industries, including the agricultural and construction sectors.

There is also the question of secondary microplastics, stemming from the breakdown of larger pieces of plastic when they enter the environment – other sources of ‘unintentional’ microplastics not covered by the law include fibres released when synthetic fabrics are washed, or particles eroding from car tyres. This is the concern of many environmentalists who want that the proposed restrictions need to be ‘tightened up’ before they become law.

The proposal will go to public consultation in the summer, before going through a lengthy review and assessment process; after approval, legislation by the European Commission may not come into force until 2021.