The Sand Mining Disaster. Why is it so difficult to control

If accessible, can be mined

If accessible, can be mined

A simple search for ‘sand mining’ will throw up at least a case every day across various parts of India. That should give you just a bare idea of the problems it is causing. And the difficulty the government is facing in controlling it. The scourge of illegal, and therefore, unchecked sand mining across India can be encapsulated in two phrases. High demand, and state government control. High demand, in this case, means that with the construction industry as a perennial customer, sand, and sand mining, therefore, will always be in demand. Strong market demand means that players, be they legal, or illegal, will always find it worthwhile to find out ways to meet the demand. A second factor that we gathered from our interactions is the role of state governments. State governments which invariably are resource starved, or prioritize other work over something as ‘small’ as sand mining. Or worse, where people in government actually benefit from the illegal income sand mining delivers.

Sand is a minor mineral, as defined under section 3(e) of the Mines and Minerals (Development and Regulation) Act, 1957 (MMDR Act). Section 15 of the MMDR Act empowers state governments to make rules for regulating the grant of mineral concessions in respect of minor minerals and related purposes. The regulation of grant of mineral concessions for minor minerals is, therefore, within the legislative and administrative domain of the state governments. This effectively makes state governments the sole authority responsible for the regulation and management of sustainable sand mining operations. Under the power granted to them by section 15 of the MMDR Act, State Governments have framed their own minor minerals concession rules.

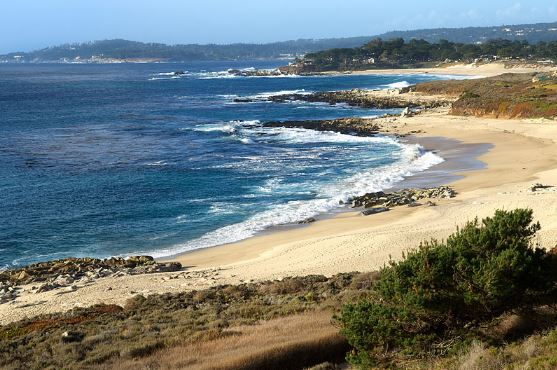

Clearly, the delegation of powers hasn’t worked in this case. With no central oversight, poorly governed states have seen sand mafias thrive, with the active connivance of local politicians and dons. Coastal states like Maharashtra, Goa, Tamil Nadu have seen serious damage to the environment from unchecked mining, as well as assaults, including murder, of local activists trying to protect their areas from the effects of sand mining.

In states like Kerala, where beach sand is proven to contain precious minerals like thorium and monazite, a recent notification prohibiting the mining of these minerals in the act of sand mining has put a halt to some of the more blatant mining that was going on.

Of course, it has been too late to save acres of land in seaside villages, that have been lost to sand mining.

Less than a week ago, the district administration of Chattarpur had to impose section 144, when it feared violence in the sand mining areas of Bundelkhand, on the bed of the Ken river. The story is similar in states like Tamil Nadu, where the high court is hearing a case demanding stricter monitoring, including check posts and installation of cameras to track the claims of miners versus actual extraction. A figure that is widely disputed in practically every state. The low cost of extraction, as well as poor monitoring, has invariably lead to over exploitation in every single state of the country.

What is the way out? A firm engaged in sand mining in Haryana claims that as long as there is demand, and no other option to cut down on sand usage, the government simply has to ensure it regulates mining more effectively. Options like the recycling of building materials are not practical, due to cost constraints. Tagging trucks used in the business, as well as restricting uthe se of high capacity trucks and equipment is another option. Most importantly it is the end users who need to be ready to pay more for sand, to ensure more efficient usage.

But with an infrastructure building spree in progress, sustainable sand mining in India remains a massive challenge crying for attention. Until then, it will continue to claim victims, both from violence and the damage it does to the environment.