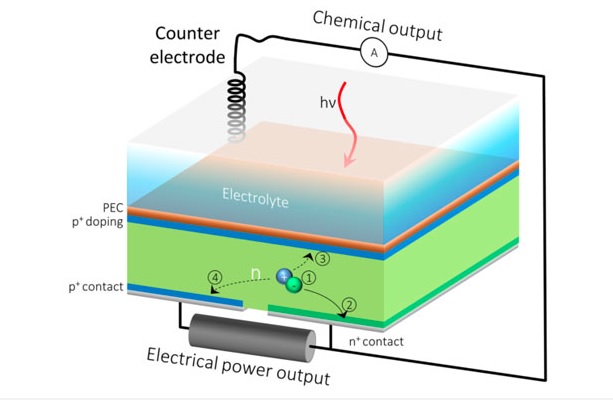

A Dual Function Solar Cell Generating Electricity and Hydrogen Fuel

Researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) renowned for having 12 researchers associated with it win the Nobel Prize and for important discoveries like the elements “Berkelium” and study of “antiproton,” and the Joint Center for Artificial Photosynthesis (JCAP), a DOE Energy Innovation Hub, have come up with an artificial photosynthesis device called a “hybrid photoelectrochemical and voltaic (HPEV) cell” that turns sunlight and water into two types of energy – hydrogen fuel and electricity.

“Water-splitting” devices, which use artificial photosynthesis to generate hydrogen from water had so far lacked a design for materials with the right mix of optical, electronic, and chemical properties needed for them to work efficiently, limiting the growth of the technology.

“It’s like always running a car in first gear,” said Gideon Segev, a postdoctoral researcher at JCAP in Berkeley Lab’s Chemical Sciences Division and the study’s lead author,. “This is energy that you could harvest, but because silicon isn’t acting at its maximum power point,most of the excited electrons in the silicon have nowhere to go, so they lose their energy before they are utilized to do useful work.”

According to their calculations, a conventional solar hydrogen generator based on a combination of silicon and bismuth vanadate, a material that is widely studied for solar water splitting, would generate hydrogen at a solar to hydrogen efficiency of 6.8 percent. In other words, out of all of the incident solar energy striking the surface of a cell, 6.8 percent will be stored in the form of hydrogen fuel, and all the rest is lost.

The team of Jeffrey W. Beeman, a JCAP researcher in Berkeley Lab’s Chemical Sciences Division, and former Berkeley Lab and JCAP researchers Jeffery Greenblatt, and Ian Sharp, now a professor of experimental semiconductor physics at the Technical University of Munich in Germany plan to continue their collaboration so they can look into using the HPEV concept for other applications such as reducing carbon dioxide emissions. “This was truly a group effort where people with a lot of experience were able to contribute,” added Segev. “After a year and a half of working together on a pretty tedious process, it was great to see our experiments finally come together.”