India Mulls Subsidies for Battery Manufacturing

Miles to go Before We Drive

Miles to go Before We Drive

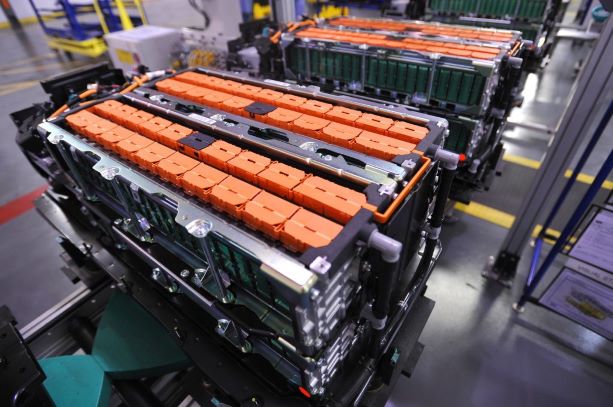

The government is working on a direct subsidy plan of about Rs 700 crores which will aim to attract Indian as well as foreign firms to play a part in domestic manufacturing of batteries. Benefits such as a 10-year subsidy (applicable on evolving technology as well) and zero import duty (Lithium, Iron, Cobalt-based EV Batteries) are also on the table.

Additionally, reports suggest that the subsidy reportedly could be proportional to the capacity committed and level of indigenisation it brings.

Government is reportedly aiming for 60 percent indigenisation by 2025. As reported earlier, NITI Aayog aims for 50 GWh of battery manufacturing to take place and competitive bids will be invited under ‘Make in India’ plan in December and projects would be awarded from 2020 based on net worth, production capacity, scale-up plan and the extent of localisation.

Companies would be expected to begin operation by 2022 and reach full committed capacity by 2025.

According to the Niti Aayog report, 1-gigawatt-hour = powering of 10 lakh homes + 30,000 EVs) battery capacity: i.e. 5 GWh per contract (10 players). The typical investment for a 10 GWh capacity factory is $1 billion.

The Winners So Far

With FAME II outlay and GST rates slashed to 5%, the only winners so far have been two wheeler companies like Okinawa, Ather and Yulu, which have used lithium-ion batteries for their EVs. FAME II incentive excluded lead-acid batteries from its ambit. This move, however, took away incentives for 95% of electric 2Ws in India.

Under FAME II, only electric two-wheelers with 50% localization can qualify for the incentives. Further, the two-wheelers should have a minimum range of 80 km per charge and minimum top speed of 40 kmph, along with riders on energy efficiency, minimum acceleration and a higher number of charging cycles.

The Cost

Lithium-ion battery manufacturing consists of the cell to battery-pack manufacturing involving a value-add of 30 to 40%, cell manufacturing with a value add of 25 to 30% and battery-chemicals with a value of 35 to 40% of the total cost of the battery pack. At the moment, cell to pack manufacturing plants has started functioning in India.

Under the FAME 2 scheme, incentives worth ₹10,000 are being offered per kilowatt of lithium- ion battery installed, with the government having sanctioned ₹10,000 crore for a period of three years for the purpose.

That’s not all. Apart from the required range and speed, automakers across categories are struggling to meet the 50% localisation target of their products to be eligible for incentives under FAME II. Most Indian vehicle manufacturers do not make lithium-ion batteries, electric motors and other specific parts used in EVs.

But companies like China-based Gemopai Electric are in the process of a complete technology transfer and are developing EVs under license in India.

Problems

- To be sure, India does not produce lithium or cobalt and will have to be import, unless it acquires mines in lithium-rich regions such as Latin America and Australia. For this, India signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with Bolivia in April and has leveraged its way into the lithium reserves of the South American nation for exploration and extraction of lithium, a prime component used to power electric vehicles. The Prime Minister’s Office wants to build an ecosystem for manufacturing electric vehicles, especially batteries, in India and does not want to repeat the outcome of the solar power generation push, which saw an import in bulk of panels from different countries rather than them being produced locally.

- Lithium-ion battery recycling industry, or urban mining: A classic chicken-and-egg problem. Despite being capital intensive, Li-ion battery industry lacks a clear path to large-scale economical recycling and battery researchers and manufacturers have traditionally not focused on improving recyclability. Instead, they have worked to lower costs and increase battery longevity and charge capacity. And because researchers have made only modest progress improving recyclability, relatively few Li-ion batteries end up being recycled.

- Charging infrastructure with battery collection: With the push on electric vehicle sales, infrastructure for charging and policy amendments to make this a viable case for consumers and their homes, the policymakers yet again have forgotten to add the element of battery collection. Since the government plans to electrify at least 30% of its vehicles and out of this about 10% of those EVS will reach the end of their service lives between now and 2030. The numbers will again be large and unlike ICE cars that go into dump yards, EVs and their components, especially batteries, will need sourcing from those points.

- Subsidies: A study by Global Subsidies Initiative (GSI) of the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) has already indicated that the subsidies given to fossil fuels is three times the total EV budget, which begs the question whether the government is serious to phase out polluting cars or is it a ‘populist’ move. Also, here is one more caveat: the GST rates have been slashed to 5% for EVs and chargers however, the GST rate on lithium batteries is still at 18%.