China’s HSR Revolution. The Green New Engine Powering It

Speeding Ahead

Speeding Ahead

Early this month, while on a tour of China to meet with key players in the renewable energy sector in the country, we ran into an unexpected issue in Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan Province. Fog had settled into the city, and flights to Hefei (1500 kms away) , the next stop on our tightly scheduled meetings, were cancelled. Suddenly, the whole schedule looked in danger of going haywire, with a cascading effect on the rest of the plans. But our organisers had other ideas.

They quickly checked, and confirmed that flights to Shanghai were available and taking off. So we quickly boarded a 3 hour flight to Shanghai (2000 kms away), and on landing at Hongqiao airport, which itself is connected to the Hongqiao railway station, the hub for HSR connections from Shanghai, we moved to a bullet train or HSR, to Hefei, just 475 kms from Shanghai. A journey that took just over 2 hours, ensuring we reached Hefei well in time for our meetings the next day. Thus, we travelled an extra 1000 kms, while starting well beyond mid-day, and still reached our eventual destination comfortably. Which made me think. Just how useful is this China HSR network proving to be ? Quite a lot, a detailed check reveals.

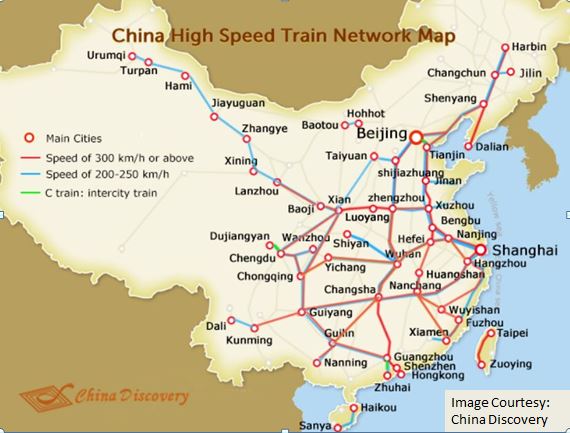

Managed and operated by the China Railway Corporation under the brand China Railway High-speed (CRH), the massive network today runs trains ranging netween speeds of 250 m/h to 350 km/h. The Beijing-Tianjin intercity rail, which opened in August 2008 and could carry high-speed trains at 350 km/h (217 mph), was the first passenger dedicated HSR line.Having opened one portion of it in 2008, the line was completed in 2013; it has reduced travel time by 20 hours and created a solid link from the Yangtze River Delta to east and south-central China. Today, the 29,000 kms (approximately) network has most of the world’s HSR firsts to its credit. Including the longest line opened in September 2018, the Beijing – Hong Kong line that connects the two key cities in ten hours .

Like most things, including our very own renewables energy, where the Chinese, once they saw the opportunity, threw everything behind it to make it a leader with over 70% global capacities today, in HSR too, China seems to have spotted the opportunity of a generation. Thus, even as naysayers predicted poor returns and other viability challenges, the country went ahead and built up the world’s largest HSR network in just over a decade, easily accounting for over 2/3rds of global HSR network today. So much so that in 2008, when the financial recession hit the world, China chose to focus its infrastructural stimulus on the HSR network, in fact.

In a World bank report on the subject, Martin Raiser, the bank’s Country Director for China says “China has built the largest high-speed rail network in the world. The impacts go well beyond the railway sector and include changed patterns of urban development, increases in tourism, and promotion of regional economic growth. Large numbers of people are now able to travel more easily and reliably than ever before, and the network has laid the groundwork for future reductions in greenhouse gas emissions,” .

The World Bank itself has financed some 2,600 km of high-speed rail in China . It’s report, China’s High-Speed Rail Development has key lessons and practices for other countries .

A key enabling factor identified by the study is the development of a comprehensive long-term plan to provide a clear framework for the development of the system. China’s Medium- and Long-Term Railway Plan looks up to 15 years ahead and is complemented by a series of Five-Year Plans.

In China, high-speed rail service is competitive with road and air transport for distances of up to about 1200 km. Fares are competitive with bus and airfares and are about one-fourth the base fares in other countries. This has allowed high-speed rail to attract more than 1.7 billion passengers a year from all income groups. Countries with smaller populations will need to choose routes carefully and balance the wider economic and social benefits of improved connectivity against financial viability concerns. Tickets on the route we too, Shanghai-Heifei, were just 299 RMB (Rs 2990 approx.), competitive with air fares, while offering higher baggage limits and comfort. Tickets on the Shanghai-Beijing leg, where 40 pairs of trains cover the 1300 km distance in well under under 5 hours, are Rs 5530 in ordinary class. This compares well with say, the distance between Delhi and Mumbai in India today, and flight tickets between the two .

A key factor keeping costs down is the standardization of designs and procedures. The construction cost of the Chinese high-speed rail network, at an average of $17 million to $21 million per km, is about two-thirds of the cost in other countries. India’s own high speed project, at around $18 million , is thankfully competitive to these costs.

The bank study also looks into the economic benefits of HSR services. The rate of return of China’s network as of 2015 is estimated at 8 percent, well above the opportunity cost of capital in China and most other countries for major long-term infrastructure investments. Benefits include shortened travel times, improved safety and facilitation of labor mobility, and tourism. High-speed networks also reduce operating costs, accidents, highway congestion, and greenhouse gas emissions as some air and auto travelers switch to rail.

According to data from the CRC itself, the number of passengers using high-speed rail exceeded that using traditional rail for the first time in 2017. Trips on the Beijing-Shanghai line have grown five fold over the past five years. Trains run every 10 minutes to 15 minutes. As one of the most profitable lines, it saw 180 million passengers in 2017, with a 12.5 per cent year-on-year growth.

Overbuilding and unviability, a major risk for high speed trains due to their high initial costs, seems to be a low risk in China, thanks to concentrated population centres and rapid industrialisation in key centres across the country.

With almost $ 725 billion of debt incurred in building out the still expanding network, returns are finally coming in, pushing back the risks of financial ruin many had been predicting for the railways.

China also went through a long period of preparation before reaching this level. It started its own “Speed-Up” campaign in the 1990’s, so that the rail networks could handle speeds that would increase from 48 km/h to 160 km/h . The first HSR line was developed from the Guangzhou-Shenzhen Railway, which was kicked up to 160 km/h in 1994 as the first sub-HSR line using diesel trains.

In 1998, the track was electrified, and Swedish X 2000 trains allowed the line to reach speeds upto 220 km/h in some sections, qualifying it as a form of HSR (200 is often considered the minimum speed for HSR). By 2007, one-fifth of the country’s railway network had been made faster, with 3,002 km of track able to reach 200 km/h and 423 km reaching 250 km/h. The trains used today are electric multiple unit trainsets, that is, sets in which one or more of the cars includes motors without the need for a dedicated locomotive, as seen in diesel-powered trains. The tracks are ballastless, meaning that traditional wooden plank road ties have been abandoned in favor of long seamless slabs of concrete with built-in ties. Though up-front costs are greater with ballastless tracks, there is less long-term maintenance and more consistency throughout the track.

Today, total riders on the network have crossed 2 billion on a network comprising almost 2800 sets of trains.

For India, its obvious where we are, when compared to the Chinese HSR system today. Somewhere where China was in 2005, with our very first HSR still three to four years away. In fact, our very own efforts to speed up the rest of the network, and launch of trains like the Vande Bharat Express and more, is strikingly similar to the Chinese . Here’s hoping that our own HSR network can provide the same impetus to greener rail travel, as the HSR has done in China.