Harnessing Sunlight to Pull Hydrogen From Wastewater

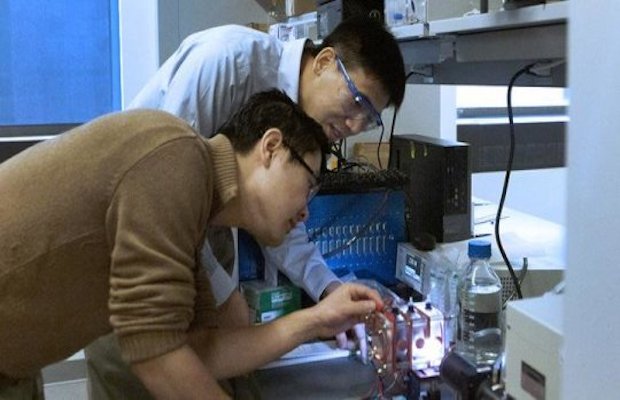

Zhiyong Jason Ren, principal investigator, and Lu Lu, first author on the study.

Zhiyong Jason Ren, principal investigator, and Lu Lu, first author on the study.

Hydrogen, which is a critical component in the manufacture of thousands of common products from plastic to fertilizers, is expensive and energy intensive to produce. But now, a team led by Zhiyong Jason Ren from Princeton University has devised an inexpensive method of creating hydrogen from wastewater.

In a study published in the journal Energy & Environmental Science, researchers from Princeton University in the US reported that their process doubled the currently accepted rate for scalable technologies that produce hydrogen by splitting water.

The technique uses a specially designed chamber with a “Swiss-cheese” black silicon interface to split water and isolate hydrogen gas. The process is aided by bacteria that generate electrical current when consuming organic matter in the wastewater; the current, in turn, aids the water splitting process.

The team ran the wastewater through the chamber, used a lamp to simulate sunlight, and watched the organic compounds breakdown and the hydrogen bubble up.

The process “allows us to treat wastewater and simultaneously generate fuels,” said Jing Gu, a co-researcher and assistant professor of chemistry and biochemistry at San Diego State University. They believe the technology could appeal to refineries and chemical plants, which typically produce their own hydrogen from fossil fuels, and face high costs for cleaning wastewater.

“It’s a win-win situation for chemical (largest producer and consumer of hydrogen) and other industries,” said Lu Lu, the first author on the study and an associate research scholar at the Andlinger Center. “They can save on wastewater treatment and save on their energy use through this hydrogen-creation process.”

According to the researchers, this is the first time actual wastewater, not lab-made solutions, has been used to produce hydrogen using photocatalysis. The team produced the gas continuously over four days until the wastewater ran out, which is significant, the researchers said, because comparable systems that produce chemicals from water have historically failed after a couple of hours of use. The researchers measured the hydrogen production by monitoring the number of electrons produced by the bacteria, which directly correlates to the amount of hydrogen produced. The measurement was at the high end for similar lab experiments and, Ren said, twice as high as technologies with the potential to scale for industrial use.

Though a lifecycle analysis has not yet been done, the researchers said the process will at least be energy neutral, if not energy positive, and eliminates the need for fossil fuels to create hydrogen.