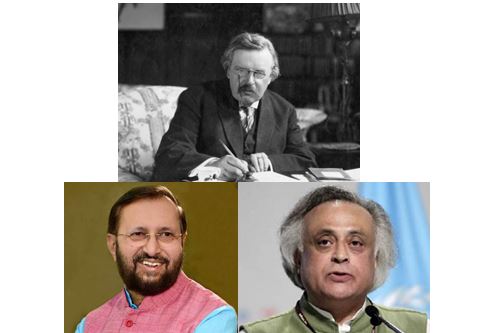

Prakash Javadekar, Jairam Ramesh and the Chesterton Fence Test

Jairam Ramesh, the former environment minister in the UPA regime, which made way for Prime Minister Modi’s government in 2014, is a peeved man today. A key policy move, which he claims to have started during his tenure as environment minister, was virtually reversed by the incumbent environment minister, Mr Prakash Javadekar recently.

An amendment to the Environmental Protection Act by a notification on May 21 , did away the requirement to ‘wash’ coal for thermal plants located more than 500 Kms from the source, ie, the coal mine. Mr Javadekar’s defence? ” How can coal become dirty after 500 kms?” A very clever retort for the lay onlooker, which is where the Chesterton Fence test comes in. So what is the test? named after English Writer GK Chesterton (Prince of Paradox), the test quite simply is a nudge towards second order thinking, unlike first order thinking. Thus, it encourages reformers, or change agents making a change to an existing setup to consider why a certain situation exists in the first place.

Or reforms should not be made until the reasoning behind the existing state of affairs is understood. Or second order thinking. Which is where Mr Ramesh’s explanation deserves attention. Referring to the current minister’s jibe on coal becoming dirty after 500 ms. Mr Ramesh claims that this was due to a planned move to gradually reduce the distance from source requirement, so as to make it easier to implement, rather than one sudden shock for miners. By removing the requirement altogether, Mr Javadekar has taken a step backward, as far as controlling pollution goes.

Thus, by failing the test of second-order thinking , or not just considering the consequences of his decisions but also the consequences of those consequences, Mr Javadekar has slipped up. Something that is all the more disappointing considering that the 500kms rule came in during the current government’s tenure, in 2016.

Mr Javadekar, who has faced criticism from activists and experts earlier too, for a seeming belief that his job is less about environment protection and more about removing any roadblocks for business from environmental safeguards, would certainly have benefited from a closer look at the story behind the rule perhaps.

At a time when the very idea of more coal mining needs to be questioned in India too, and perhaps plans made for life after coal by 2040, if not earlier, this free pass for ‘dirty’ coal is definitely not an achievement he can tout with anyone, other than the business interests who will save a little money, and cause just that extra bit of pollution. At our expense.