Biofuel sector. A waiting game

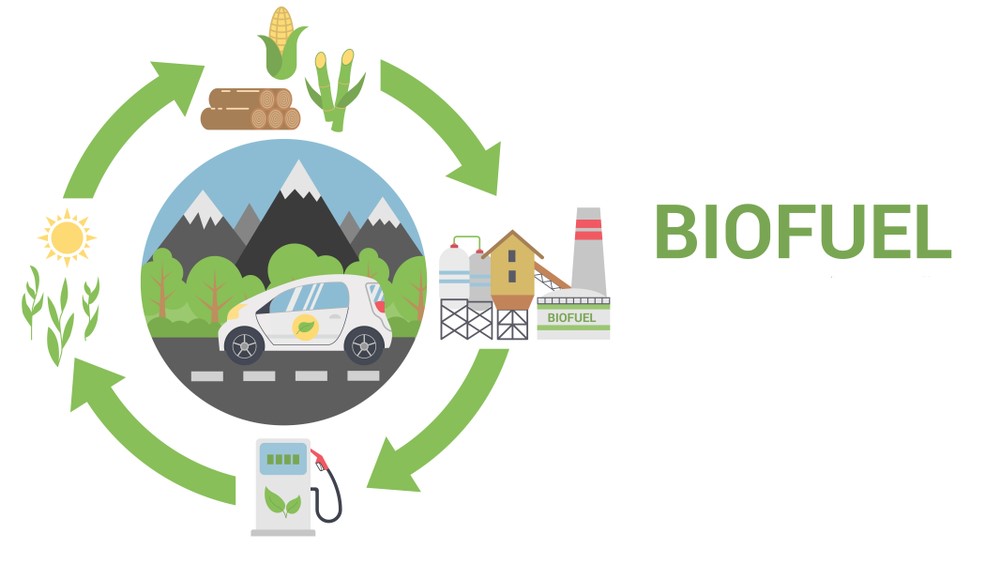

India, though an early mover in the biofuel sector, has so far failed to embrace rewards from one of the safest and cleanest of energy sources. To tap this precious resource, the Government must start formulating a strategy that actually works, instead of wishful thinking.

Connected with fluctuating oil prices , India’s biofuel sector made headlines recently with PM Modi’s announcement on World Biofuel Day on August 10, that the Government aims to develop a biofuel economy worth one trillion rupees, with state-run oil marketing companies investing Rs 10,000 crore for setting up 12 second-generation bio refineries.

He stressed upon the role of biofuels in boosting agricultural income, aiding India’s energy security and creating jobs in a cleaner environment. Later that month SpiceJet’s first experimental commercial flight from Dehradun to Delhi that ran on a combination of 25 per cent jet fuel blended with 75 per cent indigenously produced bio fuel, caught our attention.

Thats the good news. The reality of India’s Bio fuel Story is not that promising.

That can be put down to two reasons. One there has been no market creation, and linked to that, a chain of supply for biofuels yet. So Government has its task cut out for the emergence and growth of this sector. Currently, the restriction of feedstock for biofuels limit the blending to about one to three per cent only. While India has given a push for the renewable sector in the Paris Agreement, biofuel has yet to take the drivers seat in its renewable push.

First, the government should become an Architect and create necessary infrastructure and provide various supports, services or inputs for the producers.

Secondly, it should act as a controller, and define rules of the Biofuel game, ensuring adequate incentives for all stakeholders to retain long-term interests to help in development of the market.

Third, it must act as a dynamic player to not only produce the commodity, but also demonstrate to others, particularly private players. It can develop institutions to facilitate communication between various agents and incentivise farmers and other stakeholders.

However, these tasks are delicate and time-consuming, the development of the biodiesel sector hinges on how effectively the government performs and overcome its main constraints.

India’s biofuel programme encourages the use of under-utilised and degraded land to cultivate feedstock for biofuel. Although there are several sources of feedstock for biofuel, such as tree-borne oilseeds (TBOs), edible vegetable oil, animal fat and algae, the Indian Government has only emphasised on TBOs in its bio-diesel programme of 2003, and selected jatropha as the predominant plant variety.

However, Indian Government has allowed the producers to choose any TBO that suit the local conditions and that will not affect regular crop production. TBOs are planned to be cultivated in the wastelands, fallow lands, other unused Government lands. It emphasises on Sugarcane and Jatropha, both of which require huge amount of water to grow that wastelands don’t have.

Even if there is no dearth of wasteland for planting oilseeds bearing trees, locating the actual land suitable for cultivation is a difficult proposition due to ownership issues. Many of these lands are used by poor herders for grazing purposes or for collecting fuel woods or for small crops. So Government needs to ensure that the existing users’ livelihood is not snatched, and if so, alternative mechanism is placed to meet their requirements. One appropriate move could be to involve them as one of the stakeholders.

Any farmer may not originally opt for TBOs as they give yield only once a year, so Government can demonstrate its intention by designing some minimum income agreement with progressive incentive for extra production, to help allay fears of the farmer.

Also research and development for new and high-yielding plant varieties is one of the most important tasks for the Government. The state has made some arrangements for R&D and field trials involving almost all major research institutes and universities of the country for the development of jatropha plants. Based on these initial experiences with jatropha and the infrastructure created, researches can be extended to other TBOs focusing on developing locally grown plants.

In other words, it is high time to broaden the biodiesel programme to include every possible TBOs with an emphasis on using and developing local varieties. The newly-approved biofuel policy will help further. Efficient institutions capable of linking R&D centres to the demonstration of plants to farmers, information about cropping practice, risk and return as well as designing the right kind of incentives can make biodiesel programme successful.

Finally, multiplicity of value chain organisations needs to evolve in biodiesel production, where Government is already a part, a simple incentive alignment can bring all the stakeholders on one page.

Incentive in some form of ownership rights can help farmers commit to take long-term interest in fuel crops. Buy back agreement is good option with contracted price that can be adjusted when the market price goes up, and maintained to not fall below the cost of production. For the small farmers, a floor price together with incremental price for additional output would provide them an incentive to raise farm productivity. Low yield is one of the major constraints in biofuel. Apart from the high yielding plant development through R&D, there is a substantial scope for raising yield through better farm level practices.

Such moves can help the biofuel ecosystem in India to mature and bear fruits.

Bio fuel bio diesel pump detail send me sir

Tushar Mali jath 416404 Maharashtra

What’s no -7028440541

Gmail- tusharmali775@gmail.com