5 Reasons Why India Will Depend On Coal Till 2030 & Beyond

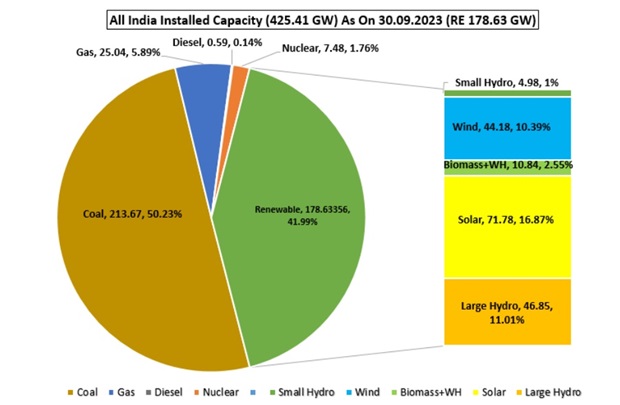

India’s renewable energy deployment in the country has increased manifolds in the last few years. As per the latest data from the Central Electricity Authority (CEA), India now has around 132 Gigawatt (GW) of renewable energy capacity (excluding hydro). The data suggest that renewable energy alone accounts for 31 percent of India’s total electricity capacity.

If hydropower is considered, 42 percent of India’s total power capacity now comes from non-fossil fuel. India plans to achieve 50 percent of its total capacity from non-fossil fuel sources by 2030. Despite this, coal demand is only expected to increase till 2030. We explain why.

The government’s estimates by the Central Electricity Authority (CEA) claimed that by 2026-27, India will have 235 GW capacity from coal-fired power, while non-fossil fuel will have 336.5 GW of capacity. It also predicts a peak demand of 277 GW. India’s peak demand in 2023 has already touched 240 GW. The overall picture hints that India will likely remain dependent on coal for its power demands.

Following are the top five reasons why India is likely to remain dependent on coal till 2030 and beyond. These reasons also highlight the difficulties in shunning coal and adopting renewable energy with open arms for India’s energy security.

India has large coal reserves to cater to the energy needs of India. Although this comes through mining and environmental degradation during the excavation, burning it for energy also adds to the burden of releasing greenhouse gases. However, countries like India are still dependent on coal for their energy security, for want of comparable cost options. According to government estimates, India has a total coal reserve of 361411.46 million tonnes. These are mainly centered in the eastern Indian states of Jharkhand, Odisha and Chattisgarh. This large deposit of coal assures the country of a firm power source to manage its energy demands and maintain a level of energy security.

The high share of Coal actually leads to an outsized impact on not just the local state economies, but even the national carrier like Indian Railways, which makes a significant chunk of its profits from transporting coal. This huge dependence on coal based revenues and employment, in states that also happen to be among the poorest in the country, makes cutting off coal use politically and socilly impossible in the near future.

Take the example of Jharkhand, India’s largest coal-producing state, which supplies around 30 percent of India’s coal. Out of 12 out of its 24 districts have operational coal mines. This ensures direct employment to millions of families besides indirect employment to several others in its coal belts.

A research report claimed that 60 percent of the transport of coal for consumption takes place through railways. On the other hand, 85 percent of the coal from mines to thermal power plants is transported through this medium. This ensures a good volume of revenue for Indian railways, compensating for the losses incurred by the railways in subsidizing its passenger fares.

For all coal-bearing states like Jharkhand, Odisha, and Chattisgarh, coal mines and thermal power plants have also paved the way for the establishment of other industries like steel. India’s steel behemoths have invested heavily in states like Jharkhand, Odisha and others. Take, for example, the famous case of the Jamshedpur steel plant in Jharkhand, and JSW steel plants at Angul in Odisha, among others. These have created a wide network of jobs and revenues for the government as well as the private sector. As government entities manage the majority of the mining activities, several of them, which are subsidiaries of CIL or other central entities, depend on coal for revenues.

India’s power demand has touched 240 GW and is expected to touch 277 GW in 2026-27 and 334 GW in 2031-32. Many power analysts opine that to maintain peak power demand, India would need firm power, which is presently possible only with its coal-fired thermal power plants. While gas based plants offer a lower emissions option, the Russia Ukraine war has effectively ruled it out at scale for India for now. Although the country is doing its best to increase the share of gas in its grid supplies. India’s former power secretary Alok Kumar, in a recent programme in New Delhi on November 20, said that coal was needed to maintain the peak demand. He claimed that maintaining peak demand with renewable energy is full of challenges.

“Governments have to take care of the peak demands and make a roadmap for managing its peak demand for 2030 unless the consumers will not tolerate blackouts. There is a need for major investments to boost infrastructure to make a grid stable using renewable energy,” he said.

Kumar said that India needed more investment for its Green Corridors, to wait for the lowering of battery storage costs, and to become less import-dependent on these storage devices to be able to make the best use of renewable energy to make itself ready to manage peak demands. “You cannot prevent the government or companies from using coal to manage its peak demand unless you have anything else to offer,” he said.

Power demand is also likely to grow robustly under almost every scenario, thanks to incremental demand that will flow in from the electrification of the transport sector. More EVs= more power demand. Like green energy corridors, India needs to evaluate a robust approach to ensuring these EVs are also powered by green energy grids where possible, again to take load off the main grid and reduce emissions faster by not using thermal energy.

Besides solar and wind in renewable energy, the use of hydro and nuclear power is projected as another option for shunning coal. However, the longer period of construction of hydropower, local community reservations against such power projects (like in Joshimath’s case and others), the government’s control over hydel projects, and its higher tariffs have become a deterrent to its increased growth. On the other hand, with the slower adoption of nuclear power, dependency on this is also far from reality. Nuclean power, for all its decent safety record and high plant load factor, is projected to account for less than 8% of the country’s power needs even in the best case scenario till 2035 and beyond. Currently, it is at barely 5%.

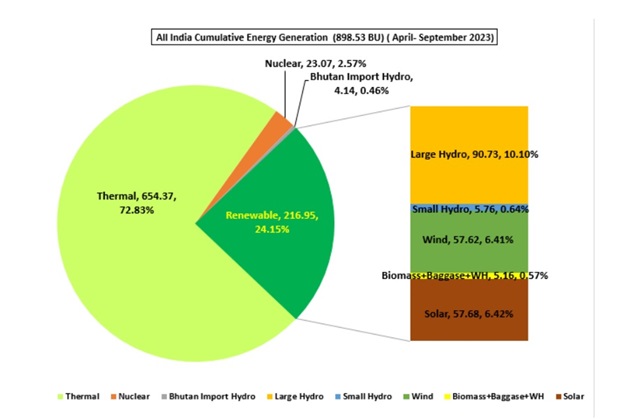

There is a stark contrast between India’s total installed capacity of power and its generation capacities. For example, the latest CEA data claimed that renewable energy accounted for 31 percent of India’s power capacity while coal accounted for 48.6 percent till October 31, 2023. However, coal accounted for around 72 percent of generation. This is because of the difference in the generation capacity of solar and wind power compared to coal. While the Plant Load Factor (PLF) of coal is around 80 percent, the CUF of solar comes to around 19-24 percent based on the modules used. Wind itself is over 30%, but intermittency remains an issue. So, despite the large installed capacity, its total generation capacity remains lower than coal.

Conclusion: It is clear that India needs at least a 20 year transition period starting now, if it is to move away from coal. And even that is a big IF, as it depends on massive investments into wind, solar, nuclear (much higher than current estimates) and most importantly, energy storage. In time, it remains to be seen if advances in distributed renewable energy in terms of cost make it viable to ensure grid quality supplies to ever larger parts and decrease the load on the national grid.

India’s cooperative sugar industry is urging the government to revise ethanol procurement prices and extend…

The Indian Biogas Association (IBA) has announced a key step taken to boost biofuels sector…

In a key development that would bolster the development of green hydrogen in the North…

Honeywell has made a key announcement wherein it has entered into a strategic collaboration with…

A biogas-based captive power plant will soon be established at the Unit-I vegetable market in…

Goa Chief Minister Pramod Sawant has laid the foundation stone for a 300 KLPD (kilolitres…